Experts reveal that with global competition rising, Europe must save its competitive edge by ramping up public funding, increasing the existing talent base, and collaborations within member states.

A European Commission strategy titled The Future of European Competitiveness highlights the urgent need for Europe to address its growing innovation gap with global leaders like the US and China.

As global investments in advanced technologies surge, experts warn that Europe risks losing its competitive edge unless it takes bold steps to strengthen public funding, expand its talent pool, and foster greater collaboration among member states.

- Time for investors to take a closer look at the digital transformation in CEE

- How Moldova’s electronics sector is attracting international brands and boosting exports

- How Poland became key to Europe’s semiconductor sovereignty

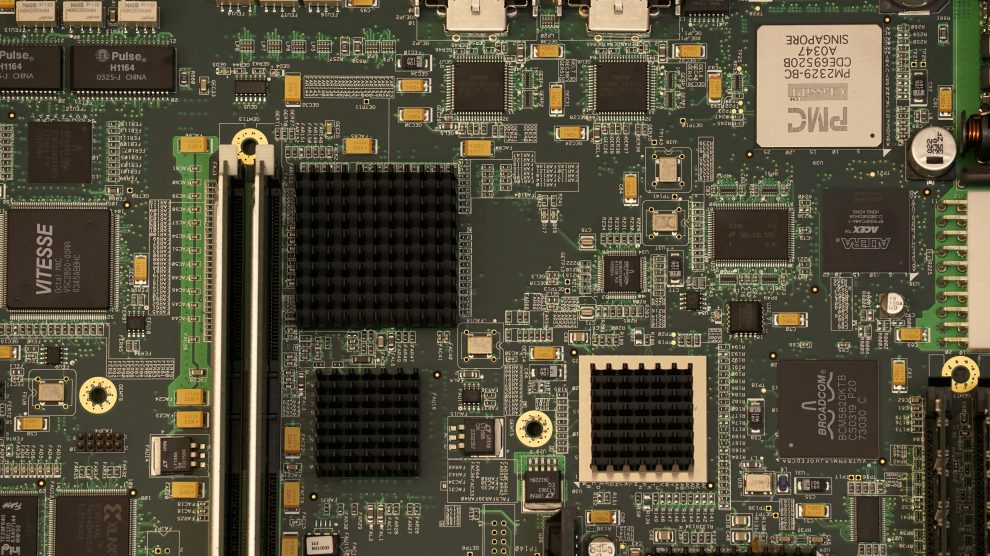

Under the EU Chips Act, 43 billion euros has been allocated to strengthen the semiconductor market. While significant, this investment is dwarfed by commitments from global competitors.

The US CHIPS Act has pledged 50 billion US dollars to incentivise domestic chip production for supply chain security, while South Korea announced tax deductions of up to 35 per cent, saving over ₩3.6 trillion (2.82 billion US dollars) in 2024 tax payments.

Meanwhile, China’s investment clusters have positioned it as one of the largest semiconductor markets in the world.

“Given the current global situation, collaboration in Europe is crucial,” says Antanas Laurutis, CEO of Altechna, an international laser optics manufacturer based in Lithuania.

“We need a long-term strategy, one that could dissolve internal barriers and allow collective management of the talent base. This is especially important when new market players are emerging in Saudi Arabia and Southeast Asia. Now, we have to compete with other markets rather than within.”

Fragmentation, bureaucracy and policy gaps threaten competitiveness

Although EU Chips Act investments are being complimented by over 100 billion euros through programmes such as Horizon Europe and Digital Europe and the national investments of member states, a lack of coordination among national policies and financing tools is causing fragmentation. This limits Europe’s competitiveness and prevents the creation of large investment pools for innovation.

According to a perspective published by Interface, if Europe were to double its market shares by 2030, it would need better policy objectives, localised investments, and a better understanding of the semiconductors ecosystem at the national level of member states.

There are signs of progress at the national level. The Netherlands recently announced a 2.5 billion euros investment in Brainport Eindhoven to strengthen the chip industry and its attractiveness in the country. The government also allocated an additional 472 million euros specifically for talent development, showcasing an established national strategy.

Laurutis points out that similar efforts should be more widespread around the EU.

“A few success stories and projects aren’t enough,” he adds. “Despite that, it’s a good example to follow—this governmental initiative was based on a clear analysis of the sector’s ecosystem, and there is an emerging hub in Europe now. We can’t stop there, and more potential cities or regions with the infrastructure, expertise, and much-needed talent could drive innovation.”

Altechna, headquartered in Lithuania, has shown how smaller EU regions can play an essential role in global supply chains. The company recently expanded to the US with the acquisition of Alpine Research Optics, underscoring the potential of smaller ecosystems to drive innovation and compete globally.

However, national strategies are not optimised yet and progress is slowed due to bureaucratic reasons. Lithuanian company Teltonika recently announced that it will halt construction of its 3.5 billion euros semiconductor facility at Molėtai, north of Vilnius. Teltonika’s CEO Arvydas Paukštys announced there is “no hope” of securing electricity needs by 2027 and processes have been extended for too long.

After the problem has been made public, Lithuania’s then prime minister, Ingrida Šimonytė and the project’s stakeholders agreed that bureaucratic hurdles are a problem, and that a solution would be found “within weeks” to restore “a project of great importance for Lithuania”.

Europe might lack over 350,000 semiconductor professionals by 2030

Bridging the talent gap remains a challenge in the European semiconductors sector, as it is estimated that around 350,000 professionals will be needed by 2030.

“We’re sure more hubs that could improve Europe’s sovereignty in the global market already exist. They just need more recognition and investments to live up to their full potential, not only privately, but also by governmental initiatives. At the same time, we need to start preparing the talent pool now,” adds Laurutis.

Similar opinions have been shared by the KPMG expert Lincoln Clark, who claims that investing in education, training, and targeted initiatives will be vital to closing this gap and attracting more businesses.

Photo by Bartosz Kwitkowski on Unsplash.

At Emerging Europe, we use an integrated approach centred around market intelligence to help organisations understand trends and strategically position themselves for success.

Learn how our solutions can help you thrive in the region:

Company and Services Overview | Strategic Advantage.

Add Comment